©

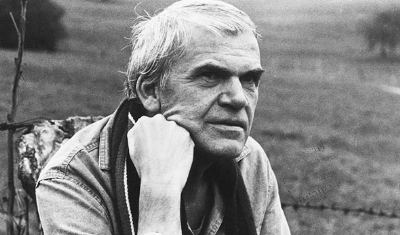

Milan Kundera has recently passed away. Discussing the legacy of this Czech-French writer, who had been writing in French since the 90s, and since the 80s he had not communicated with the media on principle (on rare occasions he did it in writing), Ukrainians today more often than others remember not his books or even the movie The Unbearable Lightness of Being starring the incomparable Juliette Binoche, but the debate that broke out in 1985 between him and Joseph Brodsky. And this is understandable: in his article Kundera hinted at a concrete link between Dostoevsky and the Soviet tanks that invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968. Kundera established the causal link not in connection with the reactionary views of the Russian classic, which, as we know, became so at a certain point in his life, but at a deeper level: in connection with his aesthetics of the hegemony of feelings.

It was a paradoxical and audacious claim, even though Kundera only touched on the subject in passing: his article actually only began with a discussion about Dostoevsky and the Soviet military, and was three-quarters devoted to other issues (Kundera’s article was entitled “An Introduction to a Variation” and was the preface to his own play). Nevertheless, even in this overture volume, his attacks on Dostoevsky did not go unheeded by one of the most prominent Soviet émigrés at the time, Joseph Brodsky. In the pages of The New York Review of Books, the Russian poet published his sharply polemical response, “Why Milan Kundera is wrong about Dostoyevsky.” Today, in 2023, Brodsky’s article, as well as Kundera’s material, may be even more relevant than when they were published. The reasons are also quite clear. Kundera raised the question of the deep connection between the aesthetics of the leading Russian classic and imperialism (Russian or Soviet—there was no difference for Kundera).

Kundera’s essay precedes his play Jacques and His Master, which he subtitled as An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts. The Czech-French writer takes Dostoevsky as a point of reference. For Kundera, this Russian classic is the best example of what he, a modern European, rejects as its polar opposite. What caused the author’s dislike of “this weight of rational irrationality”? He prefaces his motivations by recounting an episode that occurred to him in Prague on the third day after the 1968 invasion:

At one point they stopped my car. Three soldiers began searching it. Once the operation was over, the officer who had ordered it asked me in Russian, “Kak chuvstvuyetyes?”—that is, “How do you feel? What are your feelings?” His question was not meant to be malicious or ironic. On the contrary. “It’s all a big misunderstanding,” he continued, “but it will straighten itself out. You must realize we love the Czechs. We love you!”

This description is almost exactly the same as what is happening nowadays. I quote a BBC report from March 2022 (after the pro-Ukrainian rallies in Kherson):

The protesters who spoke to the military quoted them as saying: “Well, what’s wrong with you? We are here now forever. You just need to get used to it. We are protecting you, saving you, what are you doing? How can you not realize that you have been fooled here, but in reality we are the liberators.”

In his essay, Kundera, and this is what apparently hurt Brodsky, does not emphasize that the tanks, the soldiers, the invasion—everything that disfigured his country at the time—was Soviet. He wastes no time or space in distinguishing between “Russian” and “Soviet” about which, if one wished (and not without reason), one could spill a lot of ink. For Kundera, these are labels. But he is interested in the content—apparently common to both of these two products of history—and in this regard he points to one pivotal aspect: he writes about feelings, sensitivity, that is, according to Jung, “the superstructure of brutality” (in other words, the nexus of “the noblest of national sentiments”) that replaces reason and through which “commits atrocities in the sacred name of love.”

Coincidentally, it was in the days following the Soviet invasion of Prague that Kundera read Dostoevsky and concluded that he was an artist whose “feelings are promoted to the rank of value and of truth.” This was not the first time Kundera had read Dostoevsky; he had reread The Idiot in connection with a proposal to do a staged version of a novel. However, even though he was in a difficult financial situation, Kundera refused the offer:

Dostoyevsky’s universe of overblown gestures, murky depths and aggressive sentimentality repelled me. <...> What irritated me about Dostoyevsky was the climate of his novels: a universe where everything turns into feeling; in other words, where feelings are promoted to the rank of value and of truth.

And where there is a sense of possession of truth, there is also a sense that, albeit regretfully, “we’re forced to use tanks to teach them what it means to love!”

In his response essay, Brodsky primarily clings to this very thing—the eloquent conflation of tanks and culture: the writer’s encounter with a soldier of the occupation forces evokes empathy,

but only until he starts to generalize about that soldier and the culture the soldier represents. Fear and disgust are understandable, but soldiers never represent culture, let alone a literature—they carry guns, not books.

Three years after the publication of this essay, roughly the same words were uttered (in the heat of a debate in which Brodsky was very much involved) at the Lisbon Literature Conference in 1988. They were uttered by Tatyana Tolstaya, who at the same event deliberately called Brodsky a “genius,” perhaps giving away the hidden origin of her thought:

...we are not those to whom tanks obey. We are writers. And we, like all normal people, treat tanks in a very specific way. I don’t think there is anyone among us who would allow the killing of even one living soul.

Perhaps there was no such person at the above-mentioned conference, but such a person was growing up at that moment in the house of Tatyana Tolstaya herself—her son, the future famous designer Artemy Lebedev, who is not ashamed of his sympathies for Putin today. Today, Tatyana Tolstaya herself only jokes ambiguously about the war in Ukraine—so we have learned what it means to “treat tanks in a very specific way.”

Analyzing the motives of his opponent, Brodsky sees Kundera as a man who “looks feverishly around for where to put the blame.” Kundera’s finger, Brodsky writes, “pointed sharply at Dostoyevsky.” And here Brodsky, who always, unlike Kundera, uses the adjective “Soviet” rather than “Russian” when referring to tanks, points out that Kundera’s etiology is flawed, or at least not so symmetrical:

The atrocities that were and are committed in that realm, were and are committed not in the name of love but of necessity—and a historical one at that. The concept of historical necessity is the product of rational thought and arrived in Russia by the Western route.

Mentioning that Das Kapital was translated into Russian from German, the Russian poet also reminds us that “the specter of communism” has nowhere met with greater resistance than in Russia, and that this resistance began with Dostoevsky’s Demons. But Brodsky, having almost slipped into what he was familiar with as “the corrosive influence of the West,” elaborates a broader definition. He admits that “the political system that put Mr. Kundera out of commission is as much a product of Western rationalism as it is of Eastern emotional radicalism,” but ends this passage on an affirmative note: “In short, on seeing a Russian tank in the street, there is every reason to think of Diderot.”

As we know, there are even fewer grounds for this than for tracing a clear connection between Marx’s criticism of political economy and Soviet imperialism: Diderot was precisely the philosopher who personally exhorted Empress Catherine to tone down the “oriental” nature of the Russian imperial court, and if his rationalism showed itself in anything, it was exactly in this. To demonstrate how far Brodsky’s accusation diverges from reality, it would not be superfluous to quote from a special study on this subject: Diderot and the Civilization of Russia by Sergey Mezin (printed in Russia, by the way, with a cover where we see a bear’s snout next to Diderot’s profile):

Diderot remained a staunch supporter of peace and saw no benefit in Russia’s policy of conquest. In a letter from The Hague (September 1774, congratulating Catherine on the conclusion of a peace treaty with the Turks (Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca), Diderot was not inclined to admire the military victories of Russia: “Repeated triumphs, no doubt, give reigns luster, but do they bring happiness?” He wrote almost directly about the need to cherish every drop of Russian blood, not to sacrifice it in the name of glory and conquest. The progress of reason, he said, brings to the fore other more humane values.

Brodsky’s “precision” is remarkable. In a confident tone, not without intellectual coquetry, he writes about something that is the opposite of reality, and all because, apparently, he acquired a taste for the then fashionable criticism of the Enlightenment, formulated by the authoritative representatives of the Frankfurt School. The logic of this criticism was deemed tasteful because it fit well into the general framework of Brodsky’s claims against Kundera, while Brodsky was equally unable and unwilling to deal with the specifics, treating critical polemics no differently than a poem: “The one who writes a poem writes it above all because verse writing is an extraordinary accelerator of conscience, of thinking, of comprehending the universe” (from Brodsky’s Nobel speech).

Kundera’s aesthetics, who was the author of the novel Slowness, in which speed is synonymous with vulgarity, is of a somewhat different kind. After rereading The Idiot, he became nostalgic for Diderot and decided to write a play based on his novel. Why did Diderot and his novel Jacques the Fatalist become the company in which the Czech writer preferred to find himself in those difficult times for him and his country? Kundera explains it this way: “But by comparison with Diderot’s other activities, wasn’t Jacques le Fataliste merely an entertainment?” Kundera immediately clarifies what kind of entertainment it is:

Let me state categorically: no novel worthy of the name takes the world seriously. Moreover, what does it mean “to take the world seriously”? It certainly means this: believing what the world would have us believe. From Don Quixote to Ulysses the novel has challenged what the world would have us believe. <…>

Then I must ask: but what does it mean “to be serious”? A person is serious if he believes in what he would have others believe.

Let us try to compare this with Brodsky’s inference on a similar occasion: “If literature has a social function, it is, perhaps, to show man his optimal parameters, his spiritual maximum.” Let us translate these formulae into an even more substantive form. Faced with the “end of the West,” Kundera does not write something like Descent into Hell, but merely speaks of the “unbearable” but still “lightness” of being. Brodsky is more serious: it goes without saying that in his case, in the context of talking about “spiritual maximum,” there can be no mention of entertainment or “lightness”: “Russians are called upon to serious business,” as the Marquis de Custine said. One could say that Kundera sees himself not only on a completely different shore, but does not find it necessary to moor to anything at all, since “from the Renaissance on, this Western sensibility has been balanced by a complementary spirit: that of reason and doubt, of play and the relativity of human affairs. It was then that the West truly came into its own.”

For Kundera, the flourishing of the West is associated with this very quality, with the realization that any “spiritual maximum” however significant it may seem, still has conditional rights. In any case, he considers the function of literature to be fulfilled there and then, when it questions something we are made to believe in—the solidity of the world, its seriousness. At the same time, Kundera is not an adherent of total deconstruction: for him, “the spirit of the novel is the spirit of complexity,” but this complexity is linked to doubt (in The Art of the Novel Kundera points out that while Proust questioned the past, Joyce questioned the present, and in this he sees their main merit as writers).

Kundera further develops his thought on the novel of the great French enlightener as follows:

Diderot creates a space never before seen in the history of the novel: a stage without scenery. Where do the characters come from? We do not know. What are their names? That is none of our business. How old are they? No, Diderot does nothing to make us believe that his characters actually exist at a given moment. In all the history of the novel, Jacques le Fataliste represents the most radical rejection of realistic illusion and of the esthetic of the “psychological” novel.

Thus Kundera questions the writer’s task of getting the truth “from under the rubble,” while Brodsky, as if these thoughts had not been expressed at all, formulates an accusation: “the West hasn’t thus far produced a writer of Dostoyevsky’s probing.” The Russian poet’s final comparison runs along similar lines: “the metaphysical man of Dostoyevsky’s novels is of greater value than Mr. Kundera’s wounded rationalist, however modern and however common.” In a certain sense, one can agree with Brodsky. We should, however, speak not of the value of the subject Brodsky calls the “metaphysical man,” but of the value of knowledge about him. According to Czesław Miłosz, Dostoevsky, even at the time of writing Notes from Underground, suggested taking into account that “each person’s will (self-love) and willfulness is a destructive force that enjoys its cruelty towards others.” This knowledge of man’s “underground” (in modern terms, of his “hidden discourse”) is really important; today more than ever. Without this, it is simply impossible to understand the truly absurd and large-scale destructive strikes that Russia is inflicting on Ukraine with a brutal logic incomprehensible to the common sense, and for this reason, Dostoevsky, in particular, should not be canceled, but studied in detail as a kind of anamnesis of the patient.

Kundera did not look into this “abyss” because he was obviously healthier, lighter. Let us look again at his texts and try to find out how this “defendant” (as well as the whole West) explained his position standing accused under the article “Actions connected with insufficient digging into the depths.” Discussing in the same essay Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy, which served as a source for Diderot, Kundera writes that this work “is unserious throughout; it does not make us believe in anything: not in the truth of its characters, nor in the truth of its author, nor in the truth of the novel as a literary genre. Everything is called into question, everything exposed to doubt; everything is entertainment (entertainment without shame).”

It is said so clearly and repeatedly that there is no doubt: the “accused” (Kundera) has never even picked up a shovel, and he is reproached for the fact that the hole is not deep. Meanwhile, Brodsky prefers not to notice this, apparently believing that the lack of desire to “dig” is due to an inability to do so. Kundera, according to Brodsky—and at this point the text of his “verdict” begins to expand noticeably, addressing the “devoid of grace rational individual” per se—has clear signs of “guilty hedonism.” After pointing out the general nature of the cause-and-effect relations that confused the writer’s consciousness, Brodsky moves on to specifics: “First of all, he has been kept on a rigid esthetic diet, which betrays itself in his frequent use of the sexual metaphor for human conduct.” Here it is pertinent to recall that for Brodsky himself, as is well known, not only eroticism, but also love is not a “theme for poetry”—he is much more serious. The origins of this conscious attitude are multidimensional and go far beyond the Russian cultural roots. Exclusively as a joke, it is worth noting that during Brodsky’s childhood and teenage years in the USSR, there was a popular song from the movie Heavenly Slug (1945) with these words:

First things first, first the airplanes,

And then the girls, and then the girls.

The poet’s unique piety for aviation allows us to quote these lines with double the motivation, and if the reader sees a curious stretch in such actions, it should be recalled that Brodsky himself saw little difference between gossip and metaphysics, and considered the influence of the Tarzan movie on de-Stalinization greater than all of Khrushchev’s speeches put together.

Critics of this article by Brodsky, and they can be found among Russian speakers, write that “Brodsky, in fact, has nothing to say about either Dostoevsky or Kundera. However, he does not miss a chance to destroy Kundera with meaningless demagoguery” (I quote Asya Pekurovskaya, author of the book Unpredictable Brodsky). This remark is only partially true.

It is true because the mosaic style of this, as well as other essays by Brodsky, does indeed look—to use Brodsky’s label here, which he “awarded” to those who sympathized with the avant-garde—like a kind of deadlock (the set of heterogeneous statements seems to be a deadlock because it has neither unity nor proper consistency—we are faced here with a literary centaur). The poet’s obsequious friend Lev Losev noted that Brodsky’s “individual thoughts and impressionistic observations collide, forcing the reader’s imagination to work in the same direction as the author’s,” but in reality nothing of the sort happens: Brodsky’s text is more like the random swinging of a polemical club, bringing to mind Brodsky’s self-definition in his essay “Collector’s Item”: “A mongrel, then, ladies and gentleman, this is a mongrel speaking. Or else a centaur.” The blows that such a centaur inflicts on the target of his indignation take place only in Brodsky’s imagination: in reality, it is always a “punishment of the sea”: spectacular, but barely so.

And yet Brodsky’s essay articulates one thought that deserves to be considered in its own right: “One’s only worry may be that his notion of European civilization is somewhat limited or lopsided, since Dostoyevsky doesn’t fit into it and is identified with the threat to it.” Dostoyevsky as a threat to Western civilization? That sounds rather exotic. Meanwhile, Brodsky, deliberately simplifying Kundera’s thought and taking it to its logical limit, says something that today, after February 24, 2022, does not sound as paradoxical as it did in the years when this debate took place. Kundera, who knew Dostoevsky’s works well and who quotes from them in his other texts as examples of accurate and caustic observation, does not use such straightforward and broad definitions in his article after all. Other writers, such as Lawrence, have noted something in Dostoevsky that should be recalled at this very point: this Russian classic’s remarkable insight is mixed with disgusting perversity (I quote from Miłosz’s article “Dostoevsky and the Western Religious Imagination”). However, to filter the “mixture” of Dostoevsky’s texts and place his “striking insight” and “disgusting perversity” in separate vials seems to be a step that takes us as far away as possible from understanding the phenomenon of literature per se.

Brodsky, however, went even further in his hubris: ironically exaggerating his points and mocking his opponent, he pretended that there was no “disgusting perversity” or reactionary nature in Dostoevsky’s work at all. As in the case of Diderot, he preferred the format of the “short course,” not differing much in style from those who today, emphasizing the negative aspects of the Russian classic’s worldview, are acting in the spirit of cancel culture. Staying true to the genre of critical analysis of individual details, let us try to discern whether there is any truth in Brodsky’s statement that Dostoevsky, from Kundera’s point of view, is a threat to Western civilization, or whether it is motivated by a desire to impress the reader.

As of February 2022, it is contextually easier than ever to answer this question. Today, Russia is at war with Ukraine and directly threatens the entire West. One could argue that the legitimacy of the Russian government that started this war is questionable, and therefore the actions of the authorities—Putin in particular—do not represent the whole of Russia. The Russian commentariat elite once had a chance to show (or declare) that Russia (its culture, including Dostoevsky) is one thing, and the people who usurped the power are another. But this did not happen, even though the number and visibility of the crimes of Putin’s regime were high.

A minor but telling episode in this context was the following: in 2016, Igor Volgin, president of the Dostoevsky Foundation, proposed to Putin that he chair a committee to celebrate the writer’s 200th birthday, reminding the roundtable participants that “in the eyes of the West and the East, Dostoevsky is a symbol of Russia” (video starting from 08:10). Thus, despite the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of hybrid warfare in Ukraine (as well as the Kremlin’s other military campaigns), the Russian Kulturträger and one of the leading experts on Dostoevsky does not shun Putin, but goes for rapprochement. This raises the following question: in what ways does this trinity—Russia, Dostoevsky, and Putin—overlap, and can the boundaries of this overlap be clearly defined?

Brodsky concludes his essay by pointing out that “Western civilization and its culture, Mr. Kundera’s qualifier included, is based first of all on the principle of sacrifice, on the idea of a man who died for our sins.” Obviously, to formulate such a thing in 1985 is anachronistic. One could have spoken with such one-dimensionality and preachy pathos two hundred years ago. Western civilization can no longer be defined as one in which religious origins are decisive.

The contemporary European civilization is based first of all on a commitment “to the principles of liberty, democracy and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms and the rule of law” (I am quoting the preamble of the EU Treaty). Each of the values listed above, if it correlates with a religious source, is not reducible to it alone. If the idea of sacrifice or the image of Jesus Christ were fundamental for contemporary Europe, no one would have been ashamed to point this out in the relevant documents. However, for Brodsky it was so, and this fact brings to mind the following statement of Dostoevsky: “...if someone had proved to me that Christ is outside the truth, and indeed it were true that the truth is outside Christ, I would rather like to remain with Christ than with the truth.” It is well known that Dostoevsky’s “Russian idea”—and the Russian vision of truly European values—is based on religious grounds, thanks to which Dostoevsky is perceived as a symbol of Russia (a symbol of its isolation—almost half of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk’s three-volume book Russia and Europe was devoted to Dostoevsky and related themes).

But how does the hegemony of feelings that Kundera points to relate to the fact that Dostoevsky, and Brodsky after him, prioritized the religious aspect in their hierarchy of values (and it is all the more reasonable to ask this question in view of the fact that the invasion of Czechoslovakia was obviously carried out by atheists)?

In the small part of his article where Kundera addresses these questions, his arguments are briefly but convincingly and consistently formulated:

The elevation of sentiment to the rank of a value dates back quite far, perhaps even to the moment when Christianity broke away from Judaism. <...> A vague feeling of love (“Love God!”—the Christian imperative) supplants the clarity of the Law (the imperative of Judaism) to become the rather hazy criterion of morality.

It is no great exaggeration to say that Kundera speaks here along the lines of what the preamble to the EU Treaty formulates as “the rule of law.” Commitment to a religious feeling based on love of God—or to the feeling of a builder of communism, the quasi-religious character of which is quite obvious—for Kundera these are things too obscure to be a criterion of morality.

If we try to make a brief conclusion about the fundamental difference between the two attitudes, it is this: Kundera points to the relativity of everything—whatever one feels, even if this feeling is extremely sublime and is connected with love of God, the construction of communism or concern for the security of the country, it should not cancel out the need to follow the simple and clear requirements of the law, rules, norms. Dostoevsky, for his part, and in this he is echoed by Brodsky, sees Christ, the God-man who sacrificed himself for our sins, at the top of the hierarchy. Kundera believes that reality itself, regardless of its concreteness, can be questioned in the novel, while Brodsky sees art as a kind of metaphysical guide that will show people the way to what exists for certain. Incidentally, one of these certainties is the artist’s personal experience. Dostoevsky, who accepted “his own experience as irrefutable” (Joseph Frank, Dostoevsky. A Writer in His Time), was very far from giving relativity any value.

The sociologist Tomáš Masaryk (President of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918–1935) stated that by promoting a synthetic and universal sense of Christian all-humanity, “Dostoevsky has in mind the unification of peoples under the leadership of Russia”—a universal reunification “with all tribes of the great Aryan race” (the latter words are a quote from Dostoevsky's Pushkin Speech).

You can read the article in French here.

Edited by Pavlo Shopin

3218